Helping Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students Reach Higher Levels of Thinking

In Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DHH) education, much of our collective energy is rightly devoted to access: access to language, access to instruction, access to curriculum. Without access, learning cannot occur. However, access alone does not guarantee understanding.

A growing concern among educators, interpreters, and families is that many students, particularly those who are deaf or hard of hearing, are receiving instruction that emphasizes rote memorization and surface-level performance, while lacking opportunities to develop reasoning, abstraction, and deep conceptual understanding. Students may appear successful on quizzes or structured programs, yet struggle when asked to explain why something works, apply knowledge to new situations, or think critically beyond familiar formats.

This article argues that while language-focused tools such as the Fairview Learning program play an important and valuable role, they must be paired with intentional instructional frameworks, such as Norman Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DOK), that deliberately push students toward higher levels of thinking. Drawing from cognitive science, educational research, and influential works by Daniel Kahneman, Carol Dweck, Angela Duckworth, and John Hattie, this article offers practical guidance for helping DHH students move beyond memorization toward durable understanding and life-ready thinking.

The Role and Limits of Language Programs Like Fairview

Programs such as Fairview Learning have become widely used in DHH education for good reason. They provide:

Structured exposure to vocabulary and syntax

Visual and repetitive practice opportunities

Predictable routines that support language development

For many DHH students—particularly those with delayed language exposure—these programs are essential for building foundational linguistic knowledge. Vocabulary must be learned before it can be used; facts must be known before they can be applied.

However, the limitation arises when such programs become the endpoint rather than the starting point of instruction.

Much of Fairview and similar curricula rely heavily on recognition, repetition, and recall. Students may:

Match words to pictures

Select correct answers from limited options

Memorize definitions or sentence patterns

While these skills align with lower-level cognition, they do not automatically transfer to higher-level reasoning. Without intentional extension, students may leave these programs able to recognize language but unable to:

Explain ideas in their own words

Make inferences

Apply concepts across contexts

Think abstractly or strategically

In other words, students may gain language access without language power.

Why Higher-Level Thinking Matters for DHH Students

Research in cognitive science consistently shows that deep learning requires effortful thinking. Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow describes two systems of thought:

System 1: Fast, automatic, shallow, and reactive

System 2: Slow, deliberate, effortful, and analytical

Much of modern schooling—especially when driven by worksheets, multiple-choice formats, or automated programs—relies heavily on System 1 thinking. For DHH students, whose language processing may already demand significant cognitive effort, instruction that never intentionally activates System 2 can severely limit long-term understanding.

Similarly, Gayle H. Gregory’s The Motivated Brain emphasizes that meaningful learning occurs when students are challenged at an appropriate level—neither overwhelmed nor under-stimulated—and when instruction requires them to actively construct meaning.

Without opportunities to reason, justify, analyze, and apply, students may appear compliant and productive while developing fragile knowledge structures that collapse outside familiar contexts.

Norman Webb’s Depth of Knowledge: A Framework for Cognitive Growth

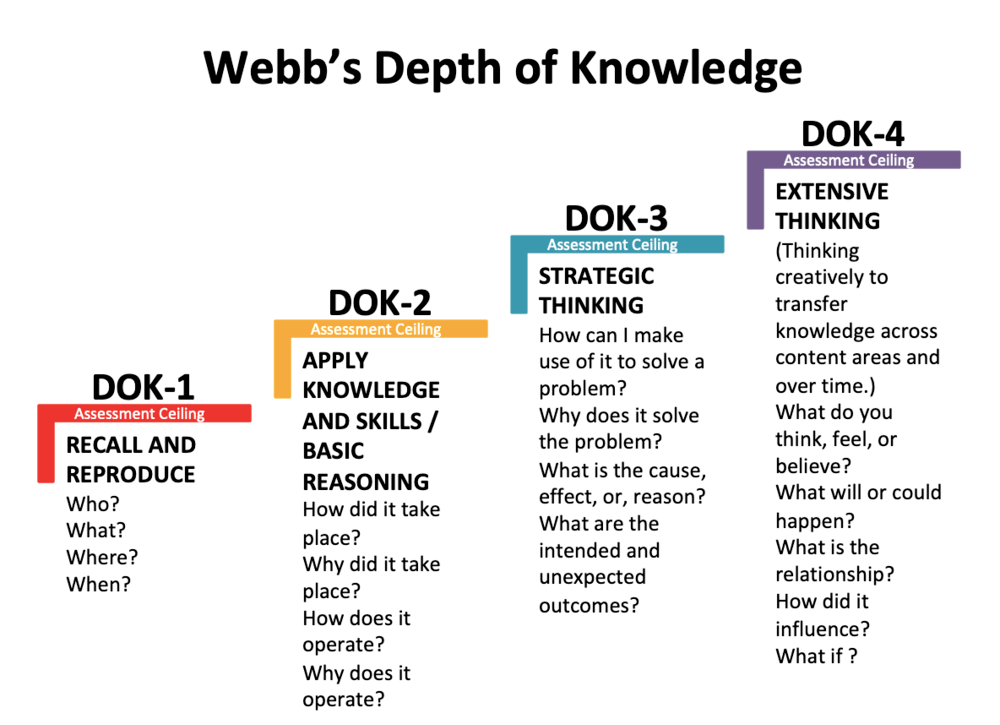

Norman Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DOK) framework offers a powerful lens for addressing this challenge. Unlike Bloom’s Taxonomy, which categorizes types of thinking, DOK focuses on the cognitive demand of tasks.

The four levels include:

DOK 1: Recall and Reproduction

Remembering facts, definitions, or proceduresDOK 2: Skills and Concepts

Explaining relationships, organizing information, applying conceptsDOK 3: Strategic Thinking

Reasoning, justifying, analyzing, and supporting ideas with evidenceDOK 4: Extended Thinking

Synthesizing, researching, applying learning over time and across domains

For DHH learners, DOK is especially valuable because it helps educators separate language difficulty from cognitive difficulty. A student may struggle to express an answer linguistically while still being capable of high-level reasoning—if given appropriate scaffolds and modes of expression.

When Tools Replace Thinking

Ironically, many students today struggle even to reach DOK 1 reliably—not because of lack of ability, but because of overreliance on external tools.

Search engines, AI tools (including ChatGPT), and digital platforms have made answers instantly available. When used thoughtfully, these tools can support learning. When used mindlessly, they short-circuit cognition.

Common patterns include:

Copying and pasting responses without processing meaning

Completing assignments without reading prompts

Submitting work that reflects no personal understanding

Even gamified platforms such as Kahoot and Blooket, designed to increase engagement, can be unintentionally misused. Some students learn to click answers rapidly without reading, relying on chance rather than comprehension. In these cases, students may earn points while bypassing thinking entirely.

For DHH students who may already experience reduced incidental learning, this pattern is particularly concerning. If students never practice retrieval, explanation, and reasoning, even basic knowledge fails to consolidate.

Mindset, Effort, and the Willingness to Think

Carol Dweck’s research on growth mindset reminds us that students must believe effort leads to improvement. When learning environments reward speed over thought, students may internalize the belief that thinking hard is unnecessary or even undesirable.

Angela Duckworth’s work on grit further reinforces that perseverance through cognitive challenge is essential for long-term success. Students who are never asked to struggle productively are not being prepared for the complexity of adult life, work, or decision-making.

John Hattie’s research on visible learning emphasizes that the most powerful instructional practices are those that make thinking visible, where students explain, reflect, and evaluate their own understanding.

Practical Ways to Support Higher-Level Thinking for DHH Students

For Teachers

Use programs like Fairview as foundations, not endpoints

Design lessons that intentionally move students across DOK levels

Ask “why” and “how,” not just “what”

Allow multiple ways for students to demonstrate understanding (ASL, writing, visuals)

For Interpreters and Aides

Understand lesson objectives and intended DOK level

Preserve cognitive complexity when interpreting—avoid simplifying thinking

Encourage student explanations rather than short answers

For Parents

Ask children to explain ideas in their own words or signs

Encourage reflection rather than correctness alone

Limit passive tool use and promote discussion

Conclusion: Preparing Students for Life, Not Just School

Helping Deaf and Hard of Hearing students reach higher levels of thinking is not about abandoning foundational programs, technology, or engagement tools. It is about using them wisely and intentionally—as supports for cognition, not replacements for it.

True success for DHH students lies not merely in completing assignments or passing assessments, but in developing the ability to:

Reason

Adapt

Analyze

Communicate ideas clearly

Make thoughtful decisions

By combining strong language access, intentional cognitive frameworks like Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, and research-informed practices from cognitive science and educational psychology, educators and families can help ensure that DHH students are not only included in classrooms—but empowered for life.